[This essay was published twenty years ago when my church, Pilgrim UCC in Carlsbad, displayed panels from the AIDS Quilt for the first of what would become many occasions. Much progress has been made on treatments for and prevention of HIV/AIDS, so it’s easy to forget that this battle is far from over. World AIDS Day is December 1.]

by Taffy Cannon

In the end, the AIDS Memorial Quilt is simply about love.

It is about beloved people gone too soon, and about those left behind to mourn. It is about memory and pain and confusion and catharsis. It is about more than 80,000 individual attempts to wrest sense out of staggering personal loss.

It is also a celebration of those commemorated, a recognition that their lives were precious and meaningful and touched others in ways that mattered.

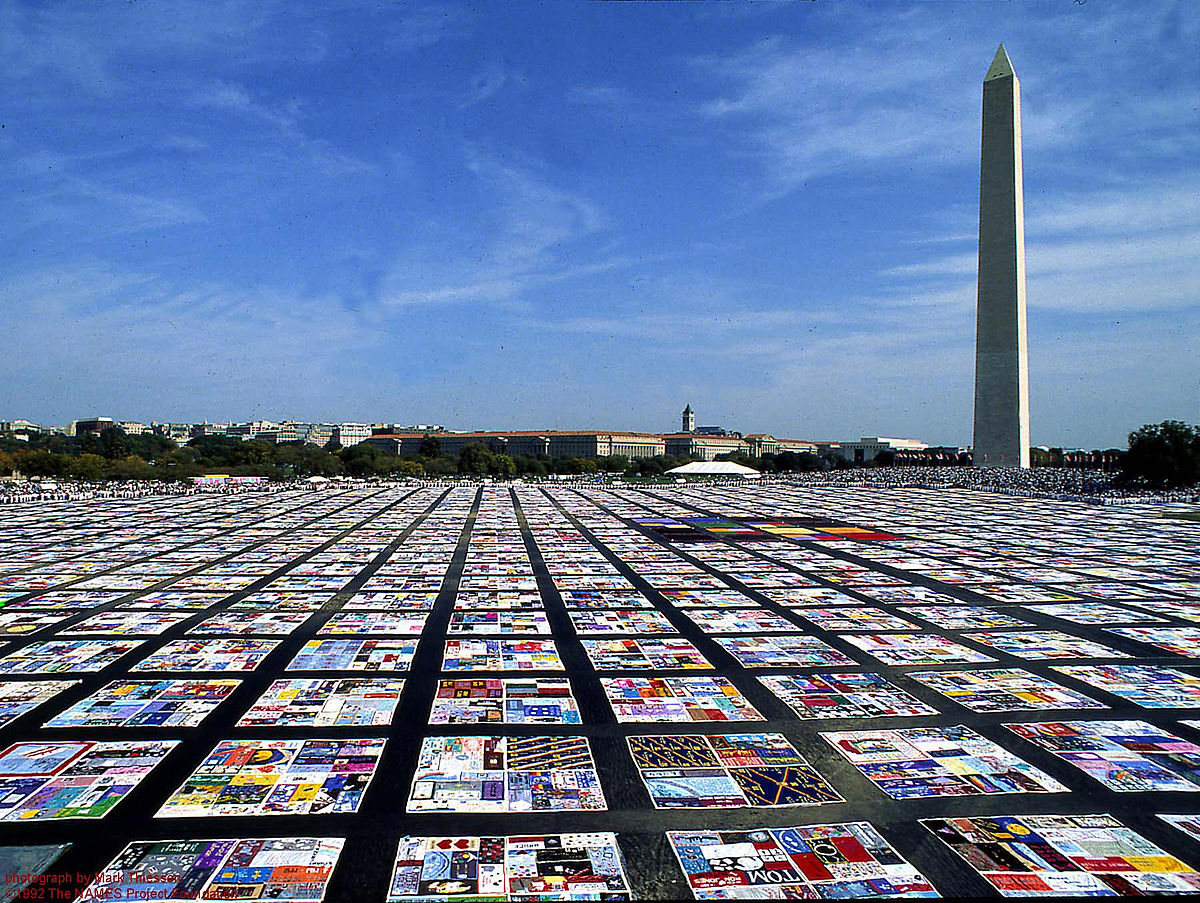

When the first grave-sized panels were sewn in 1987, nobody dreamed that the Names Project Quilt would come to cover two dozen football fields eleven years later. That the combined panels laid end-to-end would run more than fifty miles. That the quilt would become a sort of touring road show because at the end of 1998, no end to the AIDS epidemic would be in sight.

Covering the sanctuary walls of a North County church on a late November Sunday morning, a hundred panels all but reverberate with joy and sorrow. Sewn together in groups of eight, each combined section measures twelve feet square.

The panels themselves have been designed and created by those left behind, and they are as wildly varied as the folks they remember. Some are meticulously crafted with professional flair, others cheerfully funky. Some are subdued, others flamboyant. Some are achingly plain, starkly listing a name in huge, defiant letters. Others are cluttered with the detritus of lives richly lived: favorite clothing, stuffed animals, athletic jerseys, matchbooks, photographs of pets, an Illinois license plate saying SKATER.

The panel for a fashion designer features a coat he created. Another holds an actual quilt in shades of soft brown. There’s a bird of paradise and an eagle soaring above purple mountains. A large heart is inscribed within: Love Is All There Is. Many feature heartfelt final messages from parents, siblings, lovers, friends. One states simply: In memory of those who have died . . . hiding. Another notes: I could have missed the pain but I’d have had to miss the dance.

The people represented on these panels were musicians, teachers, soldiers, paramedics, actors, businessmen, doctors, lawyers. They were fathers, mothers, sons and daughters. They loved cars and beaches and rainbows and sports and art and music and each other.

What they mostly shared, besides the hideous disease which killed them, was brevity of life. On panel after panel, the numbers tell the story: 1959-93, 1961-89, 1949-88, 1957-95, 1962-93. The math is at once both simple and appallingly hard.

On Sunday, a section of the quilt was gently unfurled by young people not yet born when physicians and microbiologists began puzzling over an inexplicable new illness in the early 1980s. Any one of these teenagers might have received a tainted blood transfusion during those early days, might now be memorialized on a panel of the quilt they unfolded so carefully.

At almost any moment in America today, somebody is at work on a panel for the quilt. The quilters gather in living rooms and church basements, faculty lounges and company conference rooms. Often groups of people work together, in the historical tradition of quilting. Far too often these panels are sewn by mothers grieving children they never dreamed they would outlive. Creation moves hand in hand with catharsis.

Every panel is, of course, as unique as the person it represents. And yet throughout there runs a single and overpowering common thread.

Each and every panel is stitched with teardrops.